Implementing the Lambda Architecture

This series was written in collaboration with Boxever and first posted on Medium.

Series Overview

- Overview

- Technology, Storage and Data Format Choices

- Building the Data Lake

- The Changelog

- Batch Serving Views

- Speed Serving Views

- Merge Serving Views

Who are we?

Boxever is the Customer Intelligence Cloud for marketers. At the time of writing, we currently serve over 1 billion unique guest (user) profiles via our platform. In addition, we receive over 1 billion new events via our event streaming API every month, import 10s of millions of records via our Batch APIs, process 100s of millions of client requests via our REST APIs upon which we execute and serve 100s of millions of decisions each month. All of this results in an average of over 150 million new changelog messages being processed internally each day with peaks as much as twice this. Despite this scale, we make decisions and serve personalisations on our guest profiles with a p95 latency of 50ms! Our data volumes when we started the re architect described in this blog series were less than half of what they are today and at the time our infrastructure was starting to suffer under the load and our costs for running the service were starting to become an issue. We have a relatively small engineering team which means we must design with this in mind. This blog series will bring you through our journey and how we achieved it, from where we were to where we are now.

Where were we?

When you are a very early stage startup with everyone including the founders involved in prototyping and trying to understand the product direction, the best architecture is most often a monolithic design. This enables faster feature hacking at the early stage and reduces the time spent on the operations.

In Boxever we were no different. Initially we had a monolithic architecture both in terms of applications and databases. This central database was originally MySQL which was then migrated to Cassandra before my time. As we moved to a more microservice oriented architecture we started moving various Domain Models out of the central database and into their own per-domain model database (aka Bounded Contexts). This was great for our application level domain models but for our behavioural and transactional domain models things weren’t so simple. Behavioural data needs to be treated differently due to its velocity and volume and instead of having a single datastore, one must tier it and present it correctly for the given consumer and use case. By the time we had come to this realisation, we were already in difficulty trying to work with our behavioural data. In fact, we were in trouble trying to work with any high velocity data that we stored only in our central database.

Original Architecture

A central part to our platform and product is a concept called the Guest Context. The Guest Context is a representation of a guest (user) with all of their behavioural and transactional data attached. Think of it as an Object Graph originating at the Guest. Aggregates and statistics such as total lifetime value and total spend are also attached to the guest context. It is this rich representation that we make decisions and recommendations on in both batch and real time. All of the data available in the guest context is available as a feature for use in rules, scoring with models or templating a response. That means we need fast, random access to this data which must be capable of supporting high QPS without any performance degradation. We also require batch friendly access to this data which does not impact the real time processing. As we have over 1 billion profiles in our platform, this is a serious challenge.

With a single monolithic database, ignoring the additional flexibility and separation of concern issues, one cannot achieve the necessary data tiering when you hit a certain data growth trajectory. The size of our monolithic database was growing rapidly and its costs rising significantly just to keep pace with the current use cases. To compound these issues, the way we modelled and hence stored a large proportion of our data was not suitable for a datastore like Cassandra and caused additional strain on the cluster.

In addition to these concerns, new SLA requirements were being requested by product to ensure we served personalisations as fast as possible. The bottleneck at the time was the storage when reading and assembling the Guest Context. It had dreadful median response times, never mind the 95 percentile ranges that we needed to satisfy. Due to how we structured and stored our data for our REST APIs and how we stored behavioural data, the number of reads we needed to perform to assemble the Guest Context for decisioning was nonlinear with the number of sessions. This meant we could have hundreds, to thousands of disks seeks being triggered on the cluster to satisfy a single query. The more fragmented the Cassandra SSTables being read, the higher the number of disk seeks required, and given the larger tables are more difficult to keep compacted properly it, becomes a vicious circle. Conceptually, an optimised read of the Guest Context for decisioning would require only a single data access using the guest key. However, it is not the optimal way to store it for REST APIs. Therefore, we needed multiple “views” for reading the same data where each was optimised for the given read use case - think materialized views but you might also be familiar with the terms CQRS and Event Sourcing (the core concepts have been around for a long time).

What Architectural changes were required?

To build these materialized views we needed an architecture that would enable us to perform the following tasks easily:

- Event Sourcing

- Build new views

- Rebuild existing views

- Tiered data (i.e. recent vs historical vs archived views)

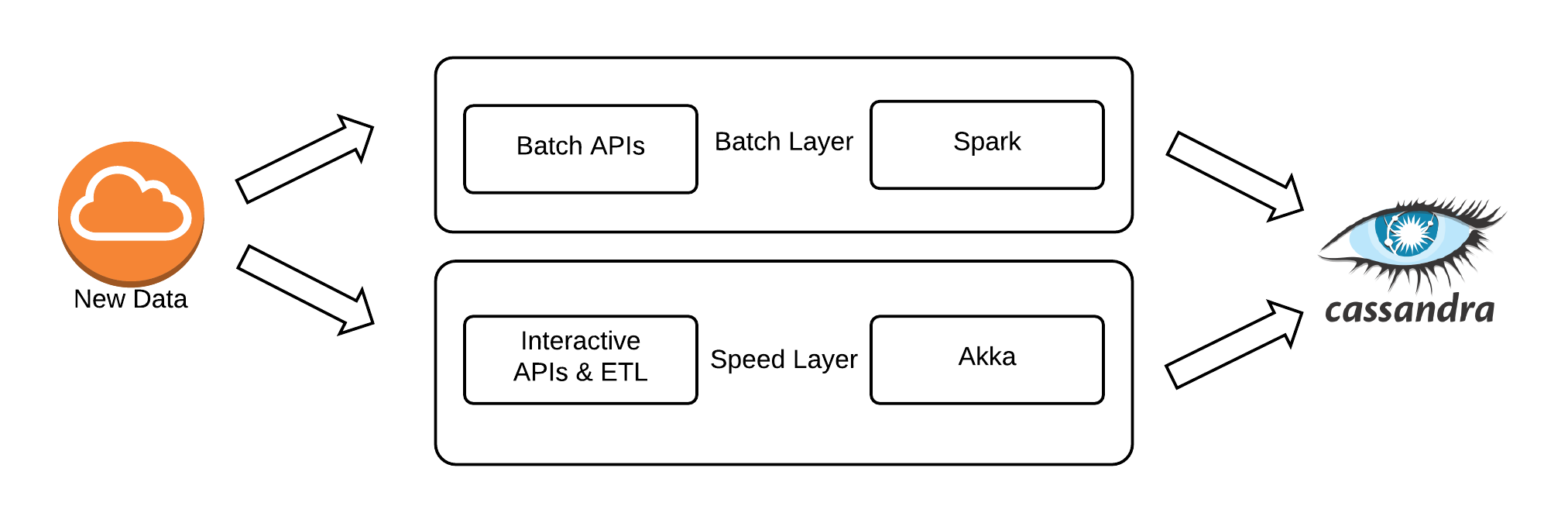

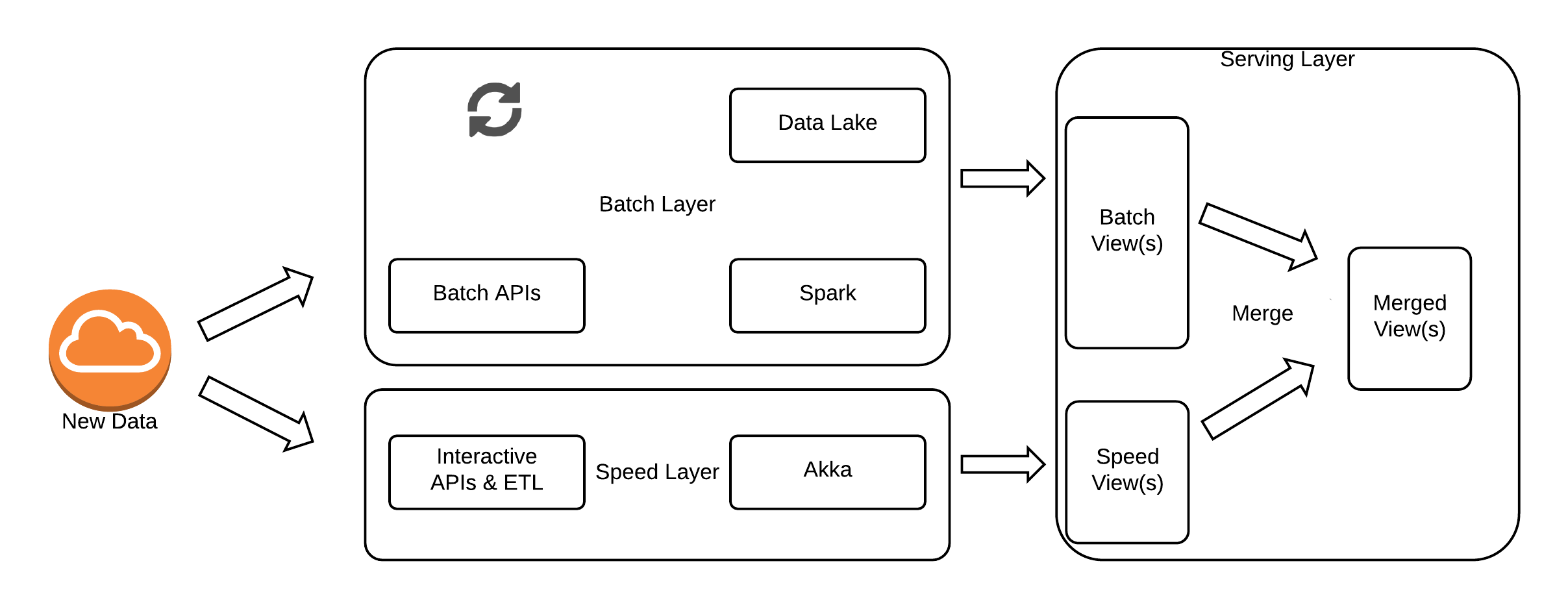

To satisfy these requirements, we decided to move towards a more Lambda Architecture. At the end of the day, the Lambda Architecture is more a set of design patterns than a prescriptive architecture and how you apply it within your own set of constraints is unique. We investigated briefly the more recent Kappa architecture that was starting to evolve out of the work LinkedIn was doing on Apache Samza. The benefits being advertised of the Kappa architecture were that everything is a stream and so you only need one codebase instead of the typical batch and stream codebases required for Lambda. At the time, support for the Kappa approach was still in its infancy and the only real tooling for it was Samza which wasn’t even an Apache incubator at that stage. Similarly, some of its key concepts rely on Kafka features like log compaction for long term scalability. Arguably, this log compaction feature is a batch process anyway which in a way brings it back to a Lambda Architecture. Similarly to ensure that you do not loose necessary change information from your event sourcing journal, you must ensure that the events are replicated to some longer term storage before compaction. As mentioned before, we have always been a reasonably small engineering team in Boxever, so we decided to go with the relatively more proven Lambda Architecture and the wealth of tooling, frameworks and resources appearing for it rather than something less proven and supported. In addition to this, frameworks such as Apache Spark and Apache Flink were starting to grow in strength and maturity which allowed for writing your logic in one framework and having it run as both batch and streaming anyway. Hence, you get some of the benefits of the Kappa Architecture while still implementing the Lambda Architecture. Regardless, we use Akka for our real time event processing pipeline as it is ideal for the stateful sessions management our pipeline requires.

Lambda Architecture

As previously discussed, the type of data and APIs we provide are not just streaming event based APIs with purely eventually consistent, asynchronous requirements. We also provide REST APIs to manage guest entities such as orders and guests within our platform in addition to application level REST APIs. These APIs have read-after-write consistency requirements which placed some restrictions on the type of designs we could choose.

These requirements roughly broke down into the following storage layers (or views):

- CRUD database for REST APIs (existing Cassandra Cluster)

- Persistent Append only Event Source Journal (Kafka)

- Data Lake File Based Storage (AWS S3)

- Low latency read-only serving layer for batch views (unknown at the time)

- Low Latency read-write serving layer for speed views (unknown at the time)

With this data tiering in place, we would only need to keep in each tier, the data that we need and only for an easily configurable duration. For instance, our Kafka TTL is typically around 3 days. We no longer keep any behavioural data in our primary Cassandra cluster and we only keep 7 days worth of data in our Speed Layer Journal. We keep all of our data permanently on S3 and then build optimised views to provide access to this data in the most efficient way possible for the given consumer.

In the next few blog posts, we will take you through how we achieved this, the challenges and the results. The posts are presented from the perspective of delivering the Guest Context in order to provide a concrete end to end use case. However, we discuss how the re architect allowed us to deliver a completely new data science and analytics platform which significantly improved our ability as a company to deliver insight from our data. We hope it will be of some benefit to others setting out on a similar journey.

Next in the series - Technology, Storage and Data Format Choices