Merging the Serving Views

This post is part of a Series on the Lambda Architecture. It was written in collaboration with Boxever and first posted on Medium.

Overview

The final part of this blog series will cover how we provide access to query and merge the various serving views in real time. If you have not read the previous posts in this series, I recommend you do so to fully understand what we will present in this post and how we arrived at this point (see Overview of Series).

Up to this point, we have covered how we built the various serving views for the Guest Context. We have described how we built both the batch and speed datasets to ensure we have access to both historic and real time changes related to a Guest. However, one of the details regarding how to implement a Lambda Architecture, which always left me confused or unsure was the merging of all these views to satisfy a query from a consumer who wants to see the single merged record. It turns out to be surprisingly simple when developed in the manner we have, and hopefully, what we present here will aid others who might have the same questions and uncertainty about the process as when we started.

Querying & Merging Architecture

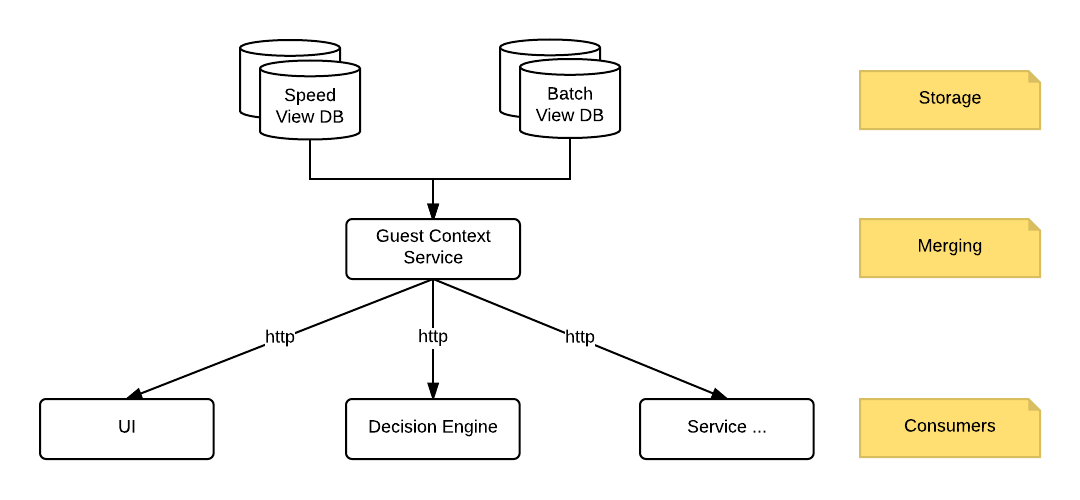

As can be seen from the diagram above, we have various services within our architecture which require access to the Guest Context. These include the UI, the decision engine and various other components. As we have a microservice based architecture, the most logical way to provide access to this merged data was via a microservice which we have aptly named the Guest Context Service.

What is Merging?

This Guest Context Service is responsible for reading from the various backend data sources and combining the data to return a single consolidated view of the current state of the Guest. This merging process was something we initially thought would be a very complex process, involving applying partial updates to entities and trying to recombine the state of an entity from various discrete pieces. Rebuilding the current state from partial updates would be quite complex and require the maintenance of logic and code that could do this for every entity in our stack. We would be re-implementing something like the Cassandra engine for computing the current state of a row. The thoughts of that were daunting - how much time, how many bugs, a maintenance nightmare. However, as we worked our way through the architecture, we realised that thanks to how we publish our changelog events, we will never have to worry about partial updates ( see our post on the Changelog ). We only ever publish the full entity states to the changelog. The merging process then became as simple as “the entity version with latest timestamp wins”. This is also similar to the premise of how the Cassandra engine works but with the one large difference being the unit of resolution is the entity itself, not an entity attribute (or column in Cassandra terms).

The Guest Context Service is a read only service which serves requests for a given Guests Context over a HTTP interface. That means it does not accept any updates to the Guest. The existing Interactive, Streaming and Batch APIs are used to update the state of a Guest. As both the batch serving view and speed serving views can have the same data (e.g. an update to an Order or some Guest attribute or identifier) the Guest Context service must query both layers to retrieve the data they contain for a given guest. Both queries can be performed in parallel and we use RxJava to simplify the operation of this (in JDK 9 there will be the concept of Flows which is based on RxJava). Note there can be any number of views that the Guest Context service can query in parallel to combine and merge the resulting Guest Context.

Merging Example

As a concrete example, we will provide sample data for a Guest whose name has recently changed and who has cancelled a previous order. The name change and the order cancellation are visible in the Speed view and so we see change log events for those. The original and historical guest name and order status are contained in the Batch view.

If you do not know how we store this change log data in the Speed view, I recommend you read the blog post on Speed Views.

Guest changelog data in Speed view

{"ref": "1", "firstName": "John", …, "modifiedAt": "2017-03-26T16:38:19.100Z"}

{"ref": "1", "firstName": "Johnny", …, "modifiedAt": "2017-03-26T16:42:59.250Z"}

Guest Order changelog data in Speed view

{"ref": "123", "status": "CANCELLED", …, "modifiedAt": "2017-03-26T16:42:00.000Z"}

We can see that we have two change log records in the speed layer for the given Guest. However, when merging we only use the record with the latest modifiedAt timestamp for entities with the same ref and we disregard the others. Therefore, when we recombine the above records, we end up with the following Guest Context in the Speed view.

{

"ref": "1",

"firstName": "Johnny",

….

"modifiedAt": "2017-03-26T16:42:59.250",

"orders": [{

"ref": "1",

"status": "CANCELLED",

…..

"modifiedAt": "2017-03-26T16:42:00.000Z"

}]

}

We then combine the Speed view with the following Guest Context from the Batch view.

{

"ref": "1",

"firstName": "John",

…..

"modifiedAt": "2017-03-24T12:18:19.100Z",

"orders": [{

"ref": "123",

"status": "PURCHASED",

…..

"modifiedAt": "2017-03-24T12:20:01.000Z"

},

{

"ref": "456",

"status": "PURCHASED",

…..

"modifiedAt": "2016-12-10T22:20:15.000Z"

}]

}

Again, performing only matching based on the modifiedAt timestamp, we produce the following merged view of the Guest Context.

{

"ref": "1",

"firstName": "Johnny",

….

"modifiedAt": "2017-03-26T16:42:59.250",

"orders": [{

"ref": "123",

"status": "CANCELLED",

…..

"modifiedAt": "2017-03-26T16:42:00.000Z"

},

{

"ref": "456",

"status": "PURCHASED",

…..

"modifiedAt": "2016-12-10T22:20:15.000Z"

}]

}

Note that in our production systems, timestamps are published and written as milliseconds since the unix epoc. We are only using ISO 8601 format here to aid in understanding the above.

Serving Views Queries

Determining which Batch View to Query (Blue-Green)

As we covered in the blog post on Batch Serving Views, we implement a blue-green deployment strategy for these views. This means that the service responsible for merging the views must be aware of which cluster is currently green and query it accordingly. For performance reasons we also want to ensure that queries are routed to the same node in this cluster always (i.e. sticky routing) so the row-cache is effective. Luckily, all of this is abstracted away from the service itself via a custom extension to the datastax driver we wrote. The switching from cluster to cluster is seamless from the services perspective. For more information on how all of this works, check out the blog post on it.

Determining the Speed Layer Query Window

As discussed in the blog post on the Speed Views, we treat the speed layer database as a time series and we keep the last 7 days of change events in it. However, we do not always want to query the full 7 days worth of data and, in fact, it would be suboptimal to do so if we only needed the last 24 hours worth.

The Guest Context Service is able to access additional meta related to the current active batch serving view. This metadata is stored in Zookeeper and contains information like the timestamp for the current active dataset (when the data for it was last prepared). The following equation is how we calculate the optimal query window to use for the speed view.

query_window_ms = now() - active_batch_dataset_ts_ms + overlap_duration_ms

The overlap duration is a safety net for data races with entities published just before midnight not being present in the batch serving view prepared for that midnight (various reasons for this but primarily how Secor is configured to upload to S3). We typically use an overlap window of 12 hours.

We use Zookeeper watches (via Apache Curator) to monitor the dataset metadata for changes. This means that if a rollback is performed on the batch serving view for any reason, we will automatically adjust our query window to take account of this. This is fantastic from an operational perspective and means that rollbacks can be seamlessly applied without any manual action required.

Wrapping Up

At the time of writing, we currently serve over 1 billion unique guest (user) profiles via our platform. In addition, we receive over 1 billion new events via our event streaming API every month, import 10s of millions of records via our Batch APIs, process 100s of millions of client requests via our REST APIs upon which we execute and serve 100s of millions of decisions each month. All of this results in an average of over 150 million new changelog messages being processed internally each day with peaks as much as twice this. Our data volumes when we started the re architect described in this blog series were less than half of what they are today and at the time our infrastructure was starting to crumble under the load (the p95 for serving personalisations was over 500ms) and our costs to run the service were becoming a concern.

Thanks to the re architect we make decisions and serve personalisations on our guest profiles with a p95 latency of 50ms! We also have a very flexible architecture where adding new views and new product use cases became an order of magnitude easier.

We delivered a completely new data science platform using Spark, Zeppelin and S3. We delivered a new analytics platform using Presto, Parquet and S3. All of this meant we transformed our ability as a company to deliver insight from our data.

We achieved all of this with a small engineering team. We hope this series has been some help in explaining the thought process and challenges we faced.

A special thanks to Pete Baron & Rodrigue Alcazar for their reviews and feedback while writing this series.